"The beginning of love is to let those we love be perfectly themselves, and not to twist them to fit our own image. Otherwise we love only the reflection of ourselves in them."

~~Thomas Merton1

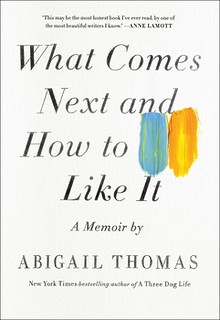

My Pap, my paternal grandfather, was a complicated man. The wickedness of his sense of humor was matched only by the wickedness of his temper. By the time of my childhood, he was mostly a quiet man, given to solitary pursuits: reading, fishing, tying flies, staring blankly at the television while rolling itty-bitty balls of Scotch tape between his index finger and thumb. When a ball got good and gummy, he would stick it under the end table next to his chair. After he died, Nan and I found thirty or forty of these little balls wadded up under there like chewing gum on the underside of a diner table.

Whole afternoons could pass in the three-room house he shared with my grandmother without us hearing the sound of his voice. He tended to be most animated around company, though whatever mysterious spirits moved him sometimes did so at unpredictable times and it would be like the sun poking out on an overcast day--if the sun were not only shiny, but quick with a raunchy2 joke and possessed of a full-throttle wheezing laugh that was equal parts disturbing and infectious. For some reason, boredom maybe, these moods would often overtake him while he was driving longish distances. He would crank Juice Newton's "The Queen of Hearts" (he had the 8-track tape of that album in the player in his car) and sing along while make goofy faces or press the accelerator in time to the music. When these moods came over him, he would ask for a smooch on his stubbly cheek, he would dole out affectionate pats and squeezes, and he could be ridiculously generous with gifts and money.

His fits of temper, like his fits of good humor, seemed to sweep out of nowhere, triggered by the teeniest things. In those moments, if his bacon was a little too crispy, he would slam his hand or, worse, fist, down hard on the nearest flat surface and the resulting smack-thud would echo through every cell in my body. He would let loose a string of profanity which rarely made much sense and in which "goddamn" and "son-of-a-bitch" figured prominently. He sometimes called my grandmother stupid or lazy. Once, I saw him drive a steak knife into a wooden table top because she had forgotten to put the butter out for his noonday meal. It was not the forgetting so much as it was her frightened attempts to apologize and explain that seemed to set him off. I never saw him lay an angry hand on my grandmother, or anyone else for that matter, but he sometimes threatened to and in those moments when he was swept away by rage, it was difficult not to be utterly convinced that he might.

For all his oversized personality, my grandfather was not a big man. Even in his youth, before drinking and smoking and steelworking and finally emphysema ground him down, he was perhaps 5'7" or 5'8" and maybe 145 pounds. By the time he died at the age of 67, the steroids which had helped him breathe had so weakened his bones that he was not quite 5'5". He weighed 87 pounds when he entered the hospital for the last time.

Despite his ever-diminishing physical stature and declining health, there was a whole stretch of time during my childhood when I thought my grandfather might be the strongest man in the world or at least in the top ten. I was convinced there was nothing he couldn't do. No doubt his ferocious temper contributed to this illusion, but that wasn't the whole of it. He had freakishly strong hands--he kept a hand exerciser within reach of his rocking chair on the end table next to his breathing machine; until I was in my early teens, there was not a jar that man could not open. He could put together any toy we pulled out of a cereal box without even looking at the directions. With his bare hands, he could pick up a hot coal that rolled out of the wood stove. (I later learned this was less of a feat of fortitude and more a function of poor circulation in his hands.) He could spell Punxsutawney.

My grandfather was an abstinent alcoholic. Though he stopped drinking when my father was very young, I do not say "recovered" or "recovering" both because he never, to my knowledge, participated in any formal recovery-type program (including AA) and because he was, in many ways, exactly the kind of man that people in the recovery community would call a "dry drunk." A dry drunk is an individual who has quit drinking or using, but has failed to adequately address underlying emotional and psychological issues that contributed to addiction in the first place, issues that are often exacerbated by years of active drinking or use.

Pap was a classic dry drunk: moody and often miserable and wholly unwilling--or, given his time and place3, likely unable--to address the source of all his bitterness. He was more than that, though. Of course he was.

Oh, how I loved that man, with his messy, outsized personality. I loved him not in spite of his faults and certainly not because of them. My love for him simply existed alongside my knowledge of his faults. It was not "I love him, but..." and not, "I love him for..." but "I love him and I'm fully aware that he's a crazy sumbitch."

The knowledge that my heart was big enough to hold pure, undiluted love and not just the awareness of, but the acceptance of a whole, real person, warts and all was an invaluable gift my grandfather gave me. That, and the love of a naughty joke--oh! and the ability to spell Punxsutawney.

|

| Pap & Me, 1968 |

1. As I was struggling with the finishing touches on this post, I clicked over to Facebook to rest my brain for a second and stumbled on this quotation, posted by one of my cousins. Timing is everything.

2. To this day, I cannot hear the Eagles' "Heartache Tonight" without hearing my grandfather's phlegmy remake of the lyrics, which, naturally, included the word "hard-on." And don't even get me started on the flag raising story, which, naturally, made great use of the phrase "blow the bugle."

3. Born February 6, 1919 just outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.